A retroactive reimagining

you could’t travel back to the 1980s.

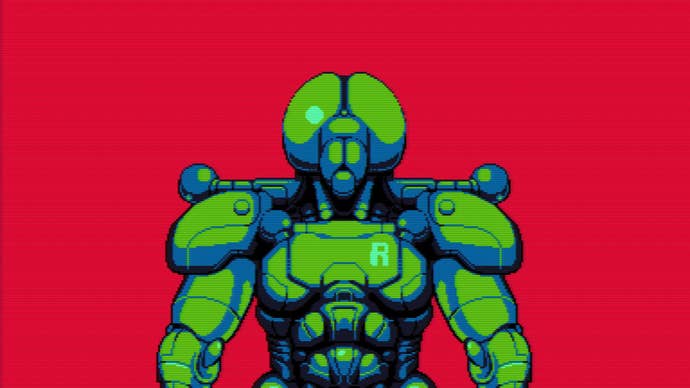

The old console, of course, is a fiction.

The LX-I never existed.

It’s an exercise in adhering to an aesthetic.

Yet play a little of each game, and you start to sense the smirk of chronos.

These games aren’t stuck in the past, but they are enjoying a holiday there.

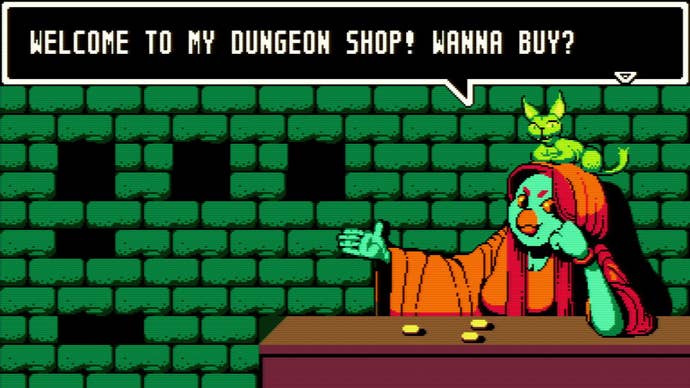

It’s also a funny collection, full of jokes and pranks at the player’s expense.

In one adventure game, tiles may fall on you without warning within seconds of your first movements.

This game is called “Attactics”; the title alone a good gag.

There’s also comedy (and satisfaction) in discovering exactly what each of these things is.

Very few of the games give you any instructions, electing instead to just drop you in.

All the direction buttons move you left, and all the face buttons move right.

Hey, why not?

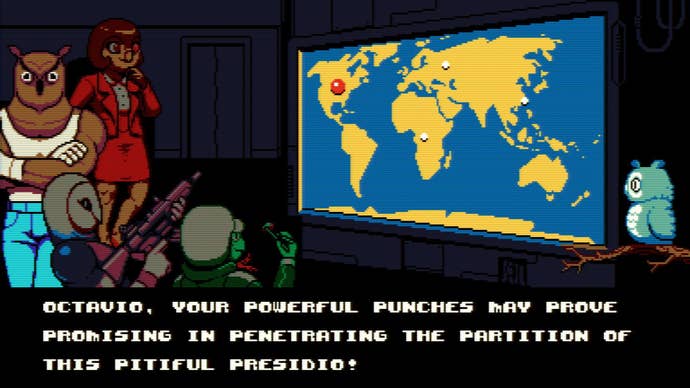

The whole collection exists in this realm of tension, stretched out like a 40-year-long rubber band.

If you squint, it’s possible for you to recognise the games of today between the pixels.

In other words, it’sNo Man’s Skybut in 1984.

Velgress is a popcorn platformer that propels you ever higher through fear of decaying platforms.

It is likeDownwellbut goingup.

After all, the designer of Downwell is onthe teamof (real) developers who made the collection.

In this I’d say they succeed.

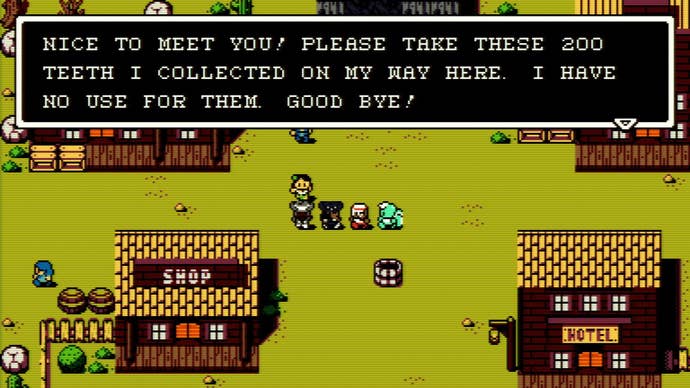

The modern twists are noticeable.

Take the concept of “lives” for example.

Mortol is a platformer in which you are given a generous 20 lives.

Other modern ideas trickle into the games.

you’re able to hold down a button to skip long cinematics, for instance.

Against the aesthetics of a pixelated era, such features feel alien, yet weirdly compelling.

Imagine you are enjoying an Akira Kurosawa flick, and suddenly: an unmistakable drone shot.

That’s what playing UFO 50 is like.

It’s a compilation of double-takes, a comic provoker of “huh"s, an anachronism bonanza.

Each game has its own short developer note.

Taking it all in at once, the compilation is the story of a hobby’s slow professionalisation.

Eventually the games start sporting a professionally animated logo, complete with a pretty jingle.

All personal calling cards are smoothed away.

Later, his name seems to disappear.

Of course, you don’t need to engage in any of this.

There is built-in curation too, letting you filter the games broadly by genre.

And even within these filters there exists a little surprise, a special screen for collectors and obsessives.

It also feels purpose-built for students of game design.

This is part of the schtick.

As someone who has spent years curating games to an audience, I’m conflicted about that.

It feels a bit like work.

I used to trawl through itch.io every week for afree games columnon this very site.

But I also didn’t get through all 50 of the games in the collection.

I barely scratched half.

I don’t think I could face mining the entire bundle.

Maybe an unfinished pile is to be expected, though.

Perhaps someone out there will explain why you should not give up on the opaque works of Thorson Petter.

That would be swell.