For Richard Garfield, creator of Magic: The Gathering and KeyForge, it’s actually quite a bit.

The computer is vital.

But he wanted autobattlers to be more ambitious.

He wanted to see one where deploying your army was as exciting as building it.

It was an order of magnitude less interesting".

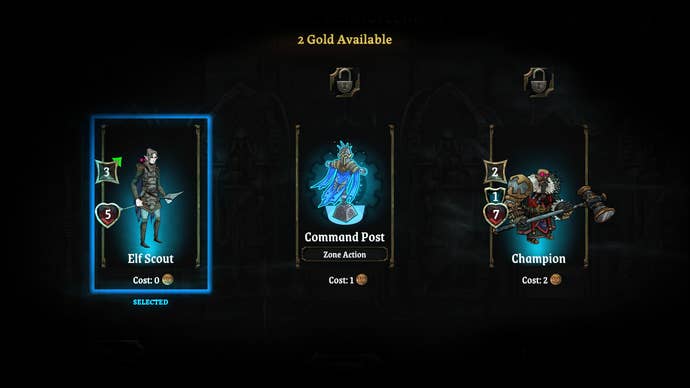

Vanguard Exiles’s proposed solution are its dungeon layouts - mazes with victory points and different room effects.

These rooms encourage players to think about unit distribution.

“Do you want to put them all in the most valuable room?

Well, if I know that, then I’ll counter by taking everything else”.

He says this leads to a style of play he hasn’t seen other autobattlers explore.

So there’s no real downtime.

“That’s good for community building and for gameplay”.

That’s the same for everybody.

He’s a fan of physicality, for one.

“So, this is one of the dangers.

So you have to understand the program you’re running.”

He gives the example of Civilization.

You don’t know how it’s making decisions.

You don’t know what’s guiding the probability.

But a lot of people play it as a black box.

“I really like the process of re-imagining these fantasy tropes into this world”.

The dwarves have a Russian slant, the elves have fur coats and employ radiation masters.

Is flavour something that Garfield usually brings in early?

He says he loves thinking about it, and exploring it once it’s been nailed down.

But at the same time, he’s very flexible.

“So this experience has not been atypical for me.

You see a dwarf unit and instinctively know he’s sturdy and reliable, I suggest.

“Exactly,” says Magic: The Gathering creator Richard Garfield, which makes me feel very clever.

We had this placeholder, we moved on to what the real thing was.

Fantasy, in general, doesn’t do that.

World War I fantasy wasn’t going to do that.

It was going to be super flexible.”

Garfield designed his first game at 13 years old, and Magic: The Gathering debuted 32 years ago.

Is he still learning?

“Oh, absolutely.

I’m learning about games, and I’m learning about players all the time.

It’s moving targets.

I mean, I get better at it, but games change all the time.

The more you know a particular game, the more it changes.

Communities change what they’re looking for, what works for them and what doesn’t.

An example is players coming up with more powerful combinations that the team expected.

But then players don’t have as much fun.”

“I don’t like to fix everything down to the point that is good for the expert.

It’s definitely an art as much as a science.”