Admittedly, some of those stat points came from mucking about with making pen and paper games as child.

When he eventually started making games professionally, those early childhood forays into game design came roaring back.

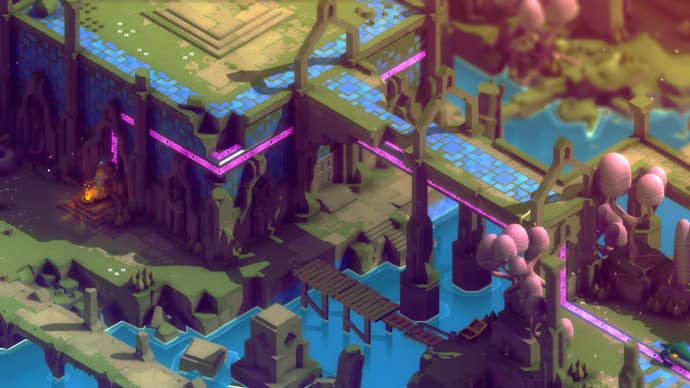

Those tools “weren’t actually appropriate for something like Tunic,” he says.

“Who knows, maybe that was the beginning of an important genesis, you know?

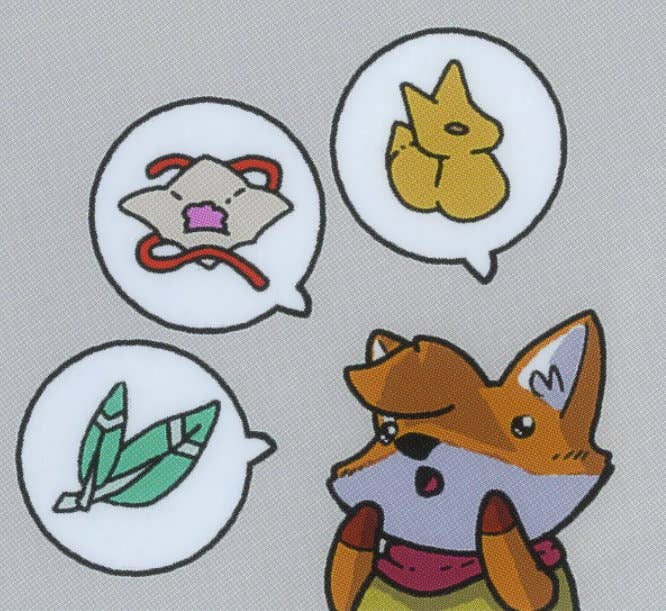

Like, ‘Oh, you need sword to chop down bush, you need key to open door.’

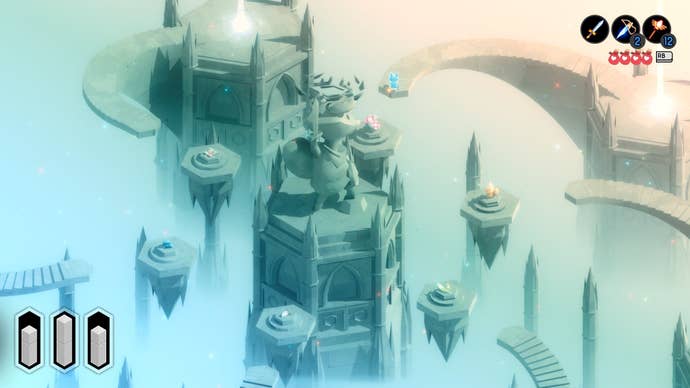

As a result, hard progression gates were out of the question.

But you probably also have a semi-critical path that you’re hoping people will find their way down.

“You start not knowing the thing.

That’s the ignorance phase.

[Then] there’s knowledge, where you know something exists but you don’t understand it.

And then eventually you do understand it.

That’s where something has clicked and you turn mystery into comprehension.

It is now a solved mystery.”

Dreaming up all of these things that were described.

But its vanilla form is still something that’s exciting to him as well, he says.

But it’s still fun to think about and try and capture that.”

“Playing games and being inspired by them is usually pretty thrilling for me,” he says.

So I saved it.

“A way to just like put stickers on places of interest or add notes or something.

Because all of that’s just fallen out.

I mean the easy answer is ‘bust out the notebook and compare the results’.

But that’s not always feasible.

Sometimes you could tell if a game is supposed to be a notebook game, sometimes you could’t.

So I think having some sort of built-in note taking capability might have been a cool thing.

Maybe not in Tunic but some other game.

It’s interesting to think about.”

Making “content for no one” is all part of the fun, he says.

Not before he’s played Tears Of The Kingdom, though.

“Who knows what comes next with that.”